|

Put Online 7 May 2024

The Times

27 August 2005

Browned off, me?

Henry Lincoln, a former Z-Cars scriptwriter, made the historical discoveries that inspired The Da Vinci Code. So, any regrets that Dan Brown made the $140 million, asks Giles Whittell

THE MAN WITHOUT WHOM ‘The Da Vinci Code’ would almost certainly not have been written seems splendidly relaxed about the fact that he didn't actually write it. The book, he says, has ‘nothing to do with the facts ... It's a potboiler, but a good one.’

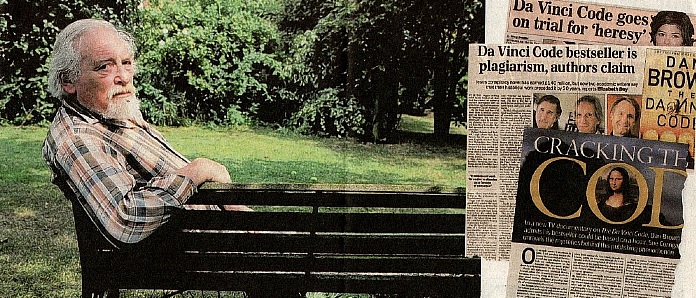

For newcomers to the planet, The Da Vinci Code is the 48-million-selling, 600-page murder mystery now being made into a Tom Hanks film about how Jesus married and had kids who moved to France and were themselves the Holy Grail. And the man who first came up with the deliciously heretical of it is Henry Lincoln, a former Z-Cars TV scriptwriter with the avuncular mieu of a successful antiques dealer and a regretful attachment to full-length Mayfair cigarettes.

Lincoln “lives in the Cotswolds” (no more detail allowed), in closely guarded privacy because of the legions of obsessives who would invade it given chance. He seldom talks to journalists, but has broken cover for this interview because The Da Vinci Code phenomenon has prompted reissue of one of his own books. As we sit in camping chairs in his “thinking place” beneath a tree at the bottom of his exquisite garden, the obvious and cruel question is whether he ever considered writing a thriller on Da Vinci Code lines himself and if so, whether this is the biggest coulda, shoulda, woulda in potboiler history.

He did, but it wasn't. Without flinching, Lincoln insists that it was a straightforward case of coulda but didn't. “I have to say that my plot was a sight more ingenious than Mr (Dan) Brown's,” he chuckles. (Brown is the former New Hampshire English teacher who is said to have made $140 million from The Da Vinci Code.) Whereas Brown grafted a doughty Harvard professor on to an otherwise European story, Lincoln says he would not have had to contrive American interest. He would have ensured it by weaving into the narrative a factual strand about one of the leading character's real-life efforts to build Arcadia in the New World in the 17th century. “But of course I don't think I'd ever have gone ahead and done it,” he adds, chuckles giving way to an engaging seriousness. “Though I started out as a drama writer, an entertainer, the discovery that I've got now is too important to trifle with.”

And thereby hangs a rather tortuous tale. It started on a Lincoln family holiday in France in 1969. “Hen”, blessed even then with a fine, patriarchal beard, was dozing off after a picnic lunch during which he had been reading, in French, Le Trésor Maudit, by Gérard de Sède. It was an ostensibly nonfiction account of the mystery of Bérenger Saunière, a 19th-century parish priest who allegedly stumbled on some ancient parchments inscribed in Latin while renovating his church at Rennes-le-Château in the north-eastern foothills of the Pyrenees. According to de Sède, Saunière took the parchments to Paris and came back an unaccountably rich man. De Sède reprinted them without much explanation, but Lincoln didn't need much. Staring idly at one of the documents, he saw in it a hidden message in French about treasure, King Dagobert II and something called Sion. On his return to England, Lincoln did some research and contacted de Sède. He later visited Rennes-le-Château and over the next ten years made a series of remarkable findings, not to mention three BBC documentaries, that led to the publication in 1996 of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, in which he and and two co-authors suggested that Jesus faked his crucifixion, married Mary Magdalene and founded a bloodline that survives to this day, protected by the Knights Templar and the keepers of all their secrets, the discreet and fabulously powerful Priory of Sion. (Saunière's sudden wealth, to cut a very long hypothesis short, derived from having stumbled on the Priory's secrets and been paid to keep them. Either that, or he had found an ancient Templar treasure removed from the Jerusalem [Temple] in 1099, or both.) It was a whopper of a thesis, which attracted global media coverage and huge book sales. The Z-Cars writer had turned Christendom upside down. Twenty years on, Dan Brown has done it again.

Much of The Da Vinci Code, from its premise to its themes and the details of its “ancient” codes, appears to be based on The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. Lincoln states bluntly, that “the story wouldn't have existed had I not made those three (BBC) Chronicle films”. But he is proprietorial only in the most informal way about the idea of a surviving Jesus bloodline, and considers the paroxysms of excitement and outrage it brings on to be cyclical things. Not so his co-authors. They are suing Mr Brown.

Plagiarism is not a ground for litigation in this country, so Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, who joined the Rennes-le-Chàteau project some time after Lincoln, are alleging copyright infringement. But it comes to the same thing. They're miffed. They are acknowledged in a bibliography in on the official Da Vinci Code website, but not in the book except in the half-anagram name of the character Leigh Teabing – a joke that may only have deepened the plaintiffs' ire as the defendant's royalties soared. Lincoln is no longer in contact with Baigent and Leigh. Nor is he a party to their lawsuit, nor will he say why. But this much is clear: The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail is not the title on his backlist that he feels most comfortable discussing. “Oh that!” he exclaims as I produce a copy. “That's 20 years out of date.”

Which is a shame. Despite its turgid prose (for which Lincoln insists Leigh is responsible) there are some spine-tingling passages in the book, particularly those on the Priory of Sion. Who couldn't be affected by the idea of Jesus's direct descendants prowling this earth as a secret society, guarding the epic treasures and, by the by, laying claim to France's ancient Merovingian throne? Especially when that society's present-day Grand Master, an aquiline Frenchman fond of detachable collars, is actually interviewed.

The trouble is, he was probably a conman. Lincoln says the Priory does crop up in the historical record as a group of Calabrian friars present at the retaking of Jerusalem in the Crusades, but it does not resurface until the mid-1950s, and then murkily, Lincoln's critics, at any rate, say he was hoaxed. The accusation infuriates him, not so much because it may be unfounded, but because it overshadows his subsequent delving into the mysteries of Rennes-le-Château. And these still visibly excite him.

Once the furore over The Blood and the Holy Grail had subsided, Lincoln returned to Rennes and found that it formed one node of a perfect five-pointed star of mountains, one of them painted by Nicolas Poussin. He called this ‘pentacle’ (oh yes, Da Vinci Code readers, Lincoln got there first) a Holy Place, and made the title of an altogether more restrained new book on the geometrical genius of the ancients, who appear to have built huge structures in the middle of it. This is his “discovery”. “In England, I'm considered a maniac,” he says, humour just about holding the line against bitterness. “Elsewhere in the world the story is taken seriously as it should be.”

And at Rennes-le-Château itself a burgeoning esoterica tourism industry, for which he accepts both blame and credit, now dominates the local economy. Lincoln says his detractors, among them the TV presenter Tony Robinson, “have done a serious disservice to scholarship. I don't care if people think I'm a fruitcake. What does matter is delaying serious study of this body of lost knowledge.”

As the breeze over the Gloucestershire hills picks up, we head inside for a cup of tea and come back once more to the Priory of Sion. He's not quite ready to let it go. “There is always the bizarre thought,” he says, fact and fiction battling as ever for his brain, “that it may all be perfectly genuine.”

The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail

by Michael Baigent, Henry Lincoln and Richard Leigh

£8.99 528pp

=========================================================

Correction published one week later:

Last week we printed the wrong book details at the end of Giles Whittell's interview with Henry Lincoln.

Lincoln's latest publication is a new edition (with new foreword) of The Holy Place.

THE HOLY PLACE: DECODING THE MYSTERY OF RENNES-LE-CHATEAU by Henry Lincoln

Arris Books, £12.99; 176pp

=========================================================

|