A sacred personage! Abbé E. HUGUET, known as Doctor (of Canon Law) Huguet, Advocate & Solicitor and Defence Counsel for Abbé Bérenger Saunière. Summoned to appear before the Court of the Officialty of Carcassonne on July 23rd 1910, Abbé Bérenger Saunière was asked to confirm the name of the lawyer he had appointed to conduct his defence, so that the Court could then decide whether or not it would give him its approval. Accordingly Saunière appointed Maître Mis, a Civil Law Advocate of the Bar of Limoux, but subsequently decided that an ecclesiastical lawyer would be better able to defend him in what was, after all, an ecclesiastical matter and therefore appointed Doctor Huguet, a priest of the Diocese of Agen, as his solicitor and defence counsel. Doctor Huguet was called upon to plead for the first time on October 15th 1910 in the 2nd Judgment of Abbé Bérenger Saunière. After his speech for the defence Dr. Huguet lodged his written pleading with the Diocesan Official. The sentence was only handed down on November 5th 1910, when both he and his client were summoned before the Court to be told that ‘Abbé Bérenger Saunière is to be punished by being ordered to enter a house of priestly retreat, there to undertake spiritual exercises of ten days' duration, and then to present himself before the Monseigneur or his deputy in order to physically present the accounting records referred to by his defence counsel during the hearing of his case’. A period of ten days was granted from notification of the sentence within which an appeal could be lodged. What happened in the next few days no one knows, except that the deadline was allowed to pass. Consequently, it would no longer be possible to intervene judicially. On the advice of Dr. Huguet, instead of ‘notifying the Officiality in writing of his intention to appeal the sentence’ Saunière started a completely new action, but this time in Rome and not before a Court (which would have been specifically the Court of Rota, which had the power to judge cases on appeal) but in front of the ‘Sacred Congregation of the Council’, which was entrusted with the task of settling disputes between members of the Clergy, Bishops or Priests. Doctor Huguet would be given the task of acting as his solicitor and defender, whereas he had been denied the right to appear before the Officialty of Carcassonne. The purpose of this step would be to address to Rome a so-called ‘recourse’ to have Abbé Bérenger Saunière reinstated as Curé of Rennes-le-Château, a post that Saunière had however given up by written resignation almost two years before, on 1st February 1909. But, for some reason unknown to us, his Lawyer appended to the file a copy of the Judgment of the Officialty of November 5th 1910 ‘not to enter an appeal against the sentence but rather to make false statements, as he said that the lawsuit had ended in acquittal and a discharge’. What this effectively said to the Sacred Congregation was that the Officialty had accepted that it was no longer competent in the matter. It should be pointed out that if Abbé Bérenger Saunière did resign then it was because his Bishop, Monseigneur de Beauséjour, had taken advantage of the fact that he was a so-called movable priest to appoint him priest-in-charge of Coustouge. Because he was unwilling to accept the change, Saunière preferred to resign.

THE NEW LAWSUIT BEFORE THE COURT OF ROME A new dossier was therefore lodged, not in Carcassonne, but on the desk of the Sacred Congregation of the Council in Rome, on December 20th 1910. At the request of the Congregation and also to clarify the matter, Dr. Huguet reduced the case to a simple demand: ‘The reappointment of Abbé Bérenger Saunière as Curé of Rennes-le-Château, around which however all the other questions would revolve’. A study of the dossier had allowed the Congregation to see that Saunière had been sentenced in Carcassonne on November 5th 1910 to enter a house of priestly retreat to undertake ten days of spiritual exercises for contravening the decree of the charging of fees for masses of Pope Pius X of May 11 1904, entitled ‘Ut debita sollicitudine’, which regulated everything concerning fees for masses, in particular the number of Masses that one can accept and the time within which they have to be said, and it therefore informed Dr. Huguet that, before anything else was done, Saunière had to fulfil the obligations imposed upon him. And so, albeit after a short delay, in April 1911 Saunière went to Prouilhe to undertake the imposed retreat, following which he sent to Rome by recorded delivery the certificate of execution of the sentence. If Saunière needed some coaxing to undertake his retreat at the monastery of Prouilhe it was primarily because of the difficulty of leaving his parish, not only because of his deep attachment to his work, which one would certainly say was very accomplished, but also because of his priestly conscience. His duties as a proprietor also forced him to postpone the date of this retreat several times. Once he had arrived at the monastery of Prouilhe – if the few letters he wrote to Marie are anything to go by – he seems to have endured his situation with calm and serenity in spite of the austerity of his retreat, which was certainly a radical change from the life he had led in his parish, although of course it only lasted a few days. It is fair to say that he kept an almost daily record of his life during this short period. As soon as he arrived he was greeted by a large dog. Abbé Berenger Saunière shared his impressions with Marie and, as a methodical man, explained how he spent every minute of his days. Through his letters, which enable us to reconstruct this period of his life in some detail, we can readily understand the atmosphere that he describes. His feelings are shared with her through his analysis of his everyday experiences as a man and as a priest. He did not seem to enjoy the loneliness; he did not like to be alone at the dinner table; and he very much appreciated the arrival of a novice who joined him for dinner several times. In his letters the priest never distances himself from religion – he is always sensitive to religious festivals and sacred places: ‘Our beautiful and uplifting Festival of the Adoration was celebrated, and celebrated splendidly’. But for Saunière food seems to be the most important thing: he often refers to it and frequently discusses his menus in detail; it is true that Marie had a reputation for being a superb cook and his pronounced taste for good food was certainly not satisfied: ‘The sin of gluttony’ indeed! Finally, and in particular, he is concerned about what is happening at home, about his rabbits, his pet animals and so on. (Claude Boumendil)

Since this first point had now been established and applied by the discharge handed down by the Court of Officialty in Carcassonne, the Congregation finally (and ‘reluctantly’) decided to study Dr. Huguet's ‘Recourse’. In this ‘Recourse’ the paramount question for the Congregation was: ‘Why did the Bishop require the removal of Abbé Bérenger Saunière so as to then appoint him Curé-in-charge at Coustouge, an appointment that Saunière refused but which was the cause of his resignation? This resignation was submitted in writing on lst February 1909, which meant that a certain length of time had passed, so why did Saunière want to return there?’ The case was certainly difficult to investigate, clear up and resolve which is why, whatever his Advocate might be asked for in the way of fresh pleadings, the matter dragged on and on and was still not resolved in 1917, the year in which Abbé Bérenger Saunière suddenly died. During his appointment to Coustouge, Saunière had written to the Bishop of Carcassonne ‘begging’ him to keep him in his parish where we had undertaken so many repairs. But a response by the Vicar-General on January 19th 1909 had informed him that his appointment had now been gazetted in the ‘Semaine Religieuse’ and the Bishop could therefore not reconsider his decision, especially as, because he no longer held the title of priest-in-charge of Rennes-le-Château, his priestly authority in that parish had automatically ceased. Saunière therefore refused his new appointment, handed in his resignation and requested that he be allowed to remain in Rennes-le-Château at the Presbytery there with the favour ‘of a private chapel’, which the Bishop refused to agree to. This was one reason why his lawyer had tried to get Rome to intervene to force the Bishop to go back on his word. In response to requests by the Congregation, Huguet increased the number of pleadings he submitted: there was one on February 21st 1911, then another in 1912, another in 1913, and another in 1914, but everyone had the impression that people were all too willing to let matters take their course, and that they were always hoping for a reconciliation, especially as the expenses (both the Court charges and the lawyer's fees) were mounting up. It was hoped that the plaintiff would eventually be forced to throw in the towel. Indeed, in December 1912 Saunière sent Huguet a genuine SOS, saying that he had had ‘to arrange a loan as a result of all the bills from the Diocese, which had used up his resources, and yet he still had large debts’. In January 1913 Dr. Huguet advised Saunière to sell the Villa Béthania ‘which would compensate him for the considerable sums he had spent, especially as he needed an unearned income to go on living in such luxury’. Nineteen Fourteen was the year of the Declaration of the Great War. On May 27th 1914 his friend Abbé Gazel, the Curé of Floure, wrote to Saunière asking ‘What stage has your court-case reached?’, asking him what he could do now, saying that he should no longer dream about it if at all possible, while deploring the money extracted from Saunière, which had served no purpose except to enable an exploitative individual (i.e. Dr. Huguet) to enjoy pleasant trips abroad. On August 8th 1915 Dr. Huguet, in spite of his various initiatives, was forced to observe that ‘the matter was still pending before the Council. Admittedly we still have the right to pursue the case in plenary session, i.e. before the Pope, but to avoid risking a possible refusal it is necessary that everything be quite clear’ (which was certainly not the case!). In August 1916 the Bishop suggested that Saunière leave Rennes to take up a post in Carcassonne: his acceptance would have made it possible for the Bishop to raise the censure on Saunière. Saunière, following Huguet's advice, refused. On January 22nd 1917, the day Abbé Bérenger Saunière died, Dr. Huguet, who was unaware of his death, wrote ‘My pleading is still with the Council: the ball is now in the Congregation's court, not mine’. This censure, imposed on December 5th 1911 by the Officialty of Carcassonne, was raised ‘in articulo mortis’ (‘at the point of death’) by Abbé Rivière, Dean of Espéraza, which enabled him to give him a religious burial in the Communal Cemetery in the Vault of the Priests which he himself had built. But who exactly was Doctor Huguet? E. Huguet was born in 1865 in Barbaste (Lot-et-Garonne). After secondary school and undergraduate studies in Law he entered the Seminary of St. Sulpice in Paris, which he left as a priest, a Doctor of Divinity and a Doctor of Canon Law. He was then appointed priest-in-charge of Espiens, a village of 430 inhabitants, in 1890, where he died on January 3rd 1927. He was an exceptional and much sought-after speaker and a fine musician. His titles of Doctor of Divinity and of Canon Law led to him being appointed a Consultor to the Court of Rome and Postulator of the Cause of the ‘Apparitions of Pellevoisin’ before the Holy Office, as well as a lawyer representing several ecclesiastics in the Diocesan Courts of the Officialty and, above all, in the Court of Appeal in Rome. It seems he enjoyed many successes, which brought him great fame. Saunière, on the recommendation of a friend, decided to entrust his case to him, and Huguet subsequently argued it both in Carcassonne and Rome. He put himself at his clients’ entire disposal, but perhaps he failed to tell Saunière the following: ‘I do not ask for fees from ecclesiastics. However I expect them to meet my travelling expenses. The frequency of my trips to Rome forces me to do this, and it's an arrangement that everyone is happy to accept’. Saunière was never slow off the mark in responding to his requests. ‘Please send me 500 francs for my travelling and accommodation expenses and my expenses in Rome, as my guest-house and transport costs easily amount to 8 or 9 francs a day’. On another occasion he would ask for 400 francs to meet the costs of rail travel, chancery, etc. etc. Generous, kind and relatively unreflective, Saunière showered his lawyer with gifts. For a Feast of the Adoration in Espiens he sent him 21(!) bottles of white and red wine, accompanied by rum from Martinique and fine champagne. On another occasion he sent 6 bottles of Crème de cacao, Curaçao, Prunelle, etc. etc. which accompanied a large box of sweet chestnuts from Castres. His role as Saunière's lawyer before the Court of the Officialty of Carcassonne was of short duration, since he was approved in October 1910 only to be removed from his post in October 1911, having entered pleadings only once during the hearing that lasted from October 15th to November 5th 1910. On the other hand he also made a number of minor appearances at the Court of Rome, something he was quick to boast about to others, and he had also had several private audiences with Pope Pius X, who he told about the many cases he had defended. He also made many friends among the Cardinals, such as Cardinal Von Rossum. But he did not enjoy the same success with the French Bishops: even his own Bishop of Montauban reportedly said (certainly tongue in cheek) that he was a ‘man who is obsessed with his job, a man who enjoys great notoriety’, and someone who ‘certainly knows the ropes’. So let's take a look at him in action in the lawsuits before the Officialty of Carcassonne and, more particularly, before the Sacred Congregation of the Council in Rome. Before the Officiality of Carcassonne Dr. Huguet had defended Saunière during its second judgment of October 5th 1910. At the end of his speech for the defence he lodged his pleadings with the Official. During the court sessions Huguet indicated that all the work that Saunière had undertaken in Rennes ‘had been paid for by voluntary or solicited assistance, because rich subscribers had been involved, not all of whom could be named, as they had been promised discretion’, and that Saunière had at the same time offered ‘a detailed statement (written in his own hand) of the subscriptions made by various people, as well as the sums billed by the contractors, which he had estimated at 193,150 francs’. For the time it was, indeed, a significant sum, and one that caused the Officialty some surprise. On the Bishop's orders a Commission was appointed to examine whether this amount was in fact correct. In a desire to shed some light on the management by Saunière the Commission sought, not without some difficulty, to obtain from Saunière by any means possible some precise details of this ‘Balance sheet of the situation’, as Saunière's lawyer had pompously termed it. However, Saunière always confined himself to simply indicating the sources of his various receipts, which his lawyer had already presented during the lawsuit. The Commission pointed out however that these were simple assertions, unsupported by any documentary evidence, and that, in particular, some of the figures struck them as incredible. Let us look at item 2 (from Saunière’s List of Donors) for example, which was entered as ‘a family lodging with me for 20 years, earning me 300 francs a month, therefore 52,000 francs in total’. Quite apart from the fact that this figure is incorrect, as 300 x 12 over 20 years makes 72,000, not 52,000 francs, the Commission (without questioning this figure, and we cannot see why they didn't!) was content to state ‘that it was surprised that a family, at that time, could earn such a considerable amount’. If we look at article 15 we see that it says: ‘The poor-box produces an average of 1,200 francs per annum and therefore over 15 years produces 18,000 francs’. ‘It strikes us as extraordinary’, the Commission says, ‘that the poor-box regularly produced such a large sum (1,200 Francs per annum)’. Saunière was then asked if he had kept a notebook or at least loose sheets recording this information and, if so, to submit them to the Commission. As for item number 25, ‘Personal work by Monsieiur Saunière for 5 years at 3 francs (which is no small amount!) per day, i.e. 3,750 francs’, and number 26, ‘Voluntary and free transportation, 4,000 francs’, the Commission wanted to know how these two items could be recorded as receipts (and in cash too). And the Commission was right to ask this! All this is enough to show that this pretty unscrupulous Advocate, Dr. Huguet, was not short of a few tricks, as he himself admitted. Moreover, the Officialty was not taken in, as after the second judgment the Court removed Dr. Huguet as Saunière’s defence advocate. The Commission was confirmed in this opinion by the discovery in Saunière's personal papers of two notes bearing the names of the donors with, at the side, the amounts they had given: the first being 71,600 Francs (‘PC’) and the second 72,100 Francs (‘LC’). However, in the ‘Balance-sheet of the situation’ drawn up in the hand of Huguet himself we find the same names (some incidentally misspelled, e.g. Monseigneur Billiard with an ‘I’ and Madame Leuzére with a ‘z’). As for the sums listed, the majority were altered and in the process inflated: so the 40,000 Francs contributed by the 2 workmen called Chapeliers becomes 52,000 Francs, the 1,000 Francs of the Countess of Chambord becomes 3,000 Francs, the 300 Francs of Monseigneur Billard becomes 200 Francs, the 10,000 Francs of Madame de Beauxhostes becomes 25,000 Francs, and so on. Can we therefore place any trust in the statements made by his lawyer? And must we not accept that this sum of 193,150 francs was based on nothing and was indeed invented for the purposes of this case by Advocate Huguet himself?

The Expenditure One wonders why a Court like the Officialty of Carcassonne not only adhered to this figure but even made it the basis of its charges against Saunière, even going as far as inviting him to present to the Court a set of accounts amounting to the figure that he himself had given during the lawsuit, i.e. 193,150 Francs. That's no problem, both the Advocate and the accused had said. So you want to know how much was spent? On July 14th 1911, helped by his lawyer, Saunière sent his Vicar-General ‘the details’, as he put it, ‘of the sums spent on the various works he had carried out’, the total for which reached 193,000 francs (we will leave the other 150 francs to one side!). Let us look at this statement of expenditure more closely: 1) – Purchase of land: 1,550 francs (but, Saunière adds, the purchase was actually made by the family that was lodging with me, who deducted the price of this acquisition from their personal income (which is why Saunière put it in the expenditure account). 2) - Restoration of the Church (interior only), namely stained glass, purchase of statues, new pulpit, new altar, new Way of the Cross, new pews, furniture for the Sacristy and ornaments, for the sum of 16,200 francs. However, the invoices lodged with the Court amounted to 5,000 francs less than that, i.e. to 11,200 francs. On the other hand, when he refers to ‘Restoration of the Calvary, 11,200 francs’, i.e. just 5,000 francs less than for the restoration of ‘the entire Church’, we are fully justified in calling the amount into question. 3) - As for the construction of the Villa Béthanie, 90,000 francs, and the Tour Magdala, 40,000 francs, the deception is even more obvious. Saunière and his lawyer simply exceeded the bounds of credibility: the Town Council spent 12,480 francs rebuilding the Elementary School which had burned down, including a classroom, the Schoolmaster's house, an enclosing wall, a covered courtyard and toilets. The Officialty could well have questioned not only all these figures but the fact that Saunière was able to balance his Income and Expenditure for 25 years of priestly ministry at Rennes-le-Château to the nearest 150 francs! |

|

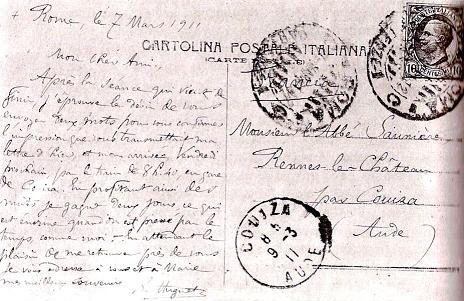

My Dear Friend, After the session that has just finished I felt a desire to send you a few words to confirm to you the impression that my letter of yesterday gave you and thus to confirm my arrival at the station in Couïza next Friday by the 8.40 am train. By taking advantage in this way of travelling by night I gain two days, which is an enormous saving when one is pressed for time, as I am. In anticipation of the pleasure of seeing you once again I send you and Marie my best wishes, E. Huguet. |